On November 27th, 2022, the 8,000th article was added to the SuccuWiki!

Mephistopheles: Difference between revisions

(New page: Category:Demon Names '''''This article on SuccuWiki has two parts. The first refers to the name often given to one representation of the devil or Satan. The second part refers...) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (6 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Demon Names]] | [[Category:Demon Names]] | ||

''For the Dungeons and Dragons deity see: [[Mephistopheles (Dungeons and Dragons)]].'' | |||

[[Image:Mephistopheles2.jpg|thumb|Mephistopheles flying over Wittenberg, in a lithograph by Eugène Delacroix.]] | |||

'''Mephistopheles''' (/ˌmɛfɪˈstɒfɪˌliːz/, <small>German pronunciation:</small> [mefɪˈstɔfɛlɛs]; also Mephistophilus, Mephistophilis, Mephostopheles, Mephisto, Mephastophilis and variants) is a demon featured in German folklore. He originally appeared in literature as the demon in the Faust legend, and he has since appeared in other works as a stock character version of the [[Devil]]. | |||

==In the Faust Legend== | |||

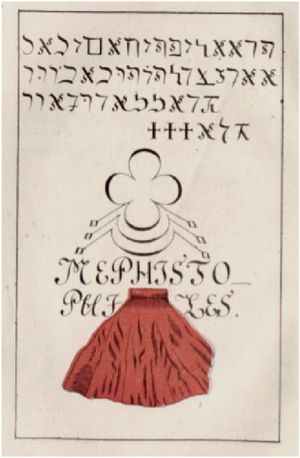

[[Image:Mephistophiles Passau 1527.jpg|thumb|right|''MEPHISTO_PHILES'' in the 1527 ''Praxis Magia Faustiana'', attributed to Faust.]] | |||

The name is associated with the Faust legend of a scholar — based on the historical Johann Georg Faust — who wagers his soul with the Devil. | |||

The name appears in the late 16th century Faust chapbooks. In the 1725 version, which Johann Wolfgang von Goethe read, ''Mephostophiles'' is a devil in the form of a greyfriar summoned by Faust in a wood outside Wittenberg. | |||

In | |||

From the chapbook, the name entered Faustian literature, many authors used it, from Christopher Marlowe to Goethe. In the 1616 edition of ''The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus'', ''Mephostophiles'' became ''Mephistophilis''. | |||

The | The word could derive from the Hebrew ''mephitz'', meaning "distributor", and ''tophel'', meaning "liar"; "tophel" is short for ''tophel shequer'', the literal translation of which is "falsehood plasterer".<ref>{{cite web |url=http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/mephistopheles |title=Mephistopheles |author=Online Etymology Dictionary |date= |work= |publisher=Dictionary.com |accessdate=4 December 2011}}</ref> The name can also be a combination of three Greek words: "me" as a negation, "phos" meaning light, and "philis" meaning loving, making it mean "not-light-loving", possibly parodying the Latin "[[Lucifer]]" or "light-bearer".<ref>The Broadview Anthology of British Literature Volume 2: The Renaissance and Early Seventeenth Century, Second Edition, ''The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus''pg. 423 (see footnote 11) ISBN 978-1-55481-028-4</ref> | ||

Mephistopheles in later treatments of the Faust material frequently figures as a title character: in Meyer Lutz' ''Mephistopheles, or Faust and Marguerite'' (1855), Arrigo Boito's ''Mefistofele'' (1868), Klaus Mann's ''Mephisto'', and Franz Liszt's Mephisto Waltzes. | |||

==Outside the Faust Legend== | |||

Shakespeare mentions "Mephistophilus" in the ''Merry Wives of Windsor'' (Act1, Sc1, line 128), and by the 17th century the name became independent of the Faust legend. According to Burton Russell,<ref name="Burton Russell 1992, p. 61">Burton Russell 1992, p. 61</ref> "That the name is a purely modern invention of uncertain origins makes it an elegant symbol of the modern [[Devil]] with his many novel and diverse forms." Mephisto is also featured as the lead antagonist in Goethe's Faust and in the unpublished scenarios for the Walpurgis night, he and [[Satan]] appear as two separate characters. | |||

== | ==Interpretations of Mephistopheles== | ||

Although Mephistopheles appears to Faustus as a [[devil]]—a worker for [[Satan]]—critics claim that he does not search for men to corrupt, but comes to serve and ultimately collect the souls of those who are already damned. Farnham explains, "Nor does Mephistophiles first appear to Faustus as a devil who walks up and down in earth to tempt and corrupt any man encountered. He appears because he senses in Faustus’ magical summons that Faustus is already corrupt, that indeed he is already 'in danger to be damned'."<ref>Farnham, Willard. Twentieth Century Interpretations of Doctor Faustus. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc.,1969: 6.</ref> | |||

Mephistopheles is already trapped in his own [[hell]] by serving the Devil. He warns Faustus of the choice he is making by "selling his soul" to the Devil: "Mephistophilis, an agent of Lucifer, appears and at first advises Faust not to forgo the promise of [[heaven]] to pursue his goals”.<ref>(Krstovic, J. O. and Marie Lazzardi. “Plot and Major Themes”. Rpt. In Literature Criticism from 1400 to 1800. Ed. Jelena O. Krstovic and Marie Lazzardi. Vol. 47. Farming Mills, MI: The Gale Group, 1999: 202) | |||

</ref> Farnham adds to his theory, “…[Faustus] enters an ever-present private hell like that of Mephistophiles”.<ref>(Krstovic 8)</ref> | |||

==References== | |||

===Bibliography=== | |||

* Burton Russell, Jeffrey, ''Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World'', Ithaca, NY: Cornell (1986); 1990 reprint: ISBN 978-0-8014-9718-6 | |||

* Hamlin, Cyrus, et al., "Faust", New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company (2001): ISBN 978-0-393-97282-5 | |||

* Ruickbie, Leo: ''Faustus: The Life and Times of a Renaissance Magician''. The History Press (2009): ISBN 978-0-7509-5090-9 | |||

===Notes=== | |||

{{Reflist}} | |||

== | |||

== | |||

== External Links == | == External Links == | ||

*[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mephistopheles The | *[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mephistopheles The original source of this article at Wikipedia] | ||

Latest revision as of 12:59, 3 September 2014

For the Dungeons and Dragons deity see: Mephistopheles (Dungeons and Dragons).

Mephistopheles (/ˌmɛfɪˈstɒfɪˌliːz/, German pronunciation: [mefɪˈstɔfɛlɛs]; also Mephistophilus, Mephistophilis, Mephostopheles, Mephisto, Mephastophilis and variants) is a demon featured in German folklore. He originally appeared in literature as the demon in the Faust legend, and he has since appeared in other works as a stock character version of the Devil.

In the Faust Legend

The name is associated with the Faust legend of a scholar — based on the historical Johann Georg Faust — who wagers his soul with the Devil.

The name appears in the late 16th century Faust chapbooks. In the 1725 version, which Johann Wolfgang von Goethe read, Mephostophiles is a devil in the form of a greyfriar summoned by Faust in a wood outside Wittenberg.

From the chapbook, the name entered Faustian literature, many authors used it, from Christopher Marlowe to Goethe. In the 1616 edition of The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus, Mephostophiles became Mephistophilis.

The word could derive from the Hebrew mephitz, meaning "distributor", and tophel, meaning "liar"; "tophel" is short for tophel shequer, the literal translation of which is "falsehood plasterer".[1] The name can also be a combination of three Greek words: "me" as a negation, "phos" meaning light, and "philis" meaning loving, making it mean "not-light-loving", possibly parodying the Latin "Lucifer" or "light-bearer".[2]

Mephistopheles in later treatments of the Faust material frequently figures as a title character: in Meyer Lutz' Mephistopheles, or Faust and Marguerite (1855), Arrigo Boito's Mefistofele (1868), Klaus Mann's Mephisto, and Franz Liszt's Mephisto Waltzes.

Outside the Faust Legend

Shakespeare mentions "Mephistophilus" in the Merry Wives of Windsor (Act1, Sc1, line 128), and by the 17th century the name became independent of the Faust legend. According to Burton Russell,[3] "That the name is a purely modern invention of uncertain origins makes it an elegant symbol of the modern Devil with his many novel and diverse forms." Mephisto is also featured as the lead antagonist in Goethe's Faust and in the unpublished scenarios for the Walpurgis night, he and Satan appear as two separate characters.

Interpretations of Mephistopheles

Although Mephistopheles appears to Faustus as a devil—a worker for Satan—critics claim that he does not search for men to corrupt, but comes to serve and ultimately collect the souls of those who are already damned. Farnham explains, "Nor does Mephistophiles first appear to Faustus as a devil who walks up and down in earth to tempt and corrupt any man encountered. He appears because he senses in Faustus’ magical summons that Faustus is already corrupt, that indeed he is already 'in danger to be damned'."[4]

Mephistopheles is already trapped in his own hell by serving the Devil. He warns Faustus of the choice he is making by "selling his soul" to the Devil: "Mephistophilis, an agent of Lucifer, appears and at first advises Faust not to forgo the promise of heaven to pursue his goals”.[5] Farnham adds to his theory, “…[Faustus] enters an ever-present private hell like that of Mephistophiles”.[6]

References

Bibliography

- Burton Russell, Jeffrey, Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World, Ithaca, NY: Cornell (1986); 1990 reprint: ISBN 978-0-8014-9718-6

- Hamlin, Cyrus, et al., "Faust", New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company (2001): ISBN 978-0-393-97282-5

- Ruickbie, Leo: Faustus: The Life and Times of a Renaissance Magician. The History Press (2009): ISBN 978-0-7509-5090-9

Notes

- ↑ Online Etymology Dictionary. "Mephistopheles". Dictionary.com. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/mephistopheles. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ The Broadview Anthology of British Literature Volume 2: The Renaissance and Early Seventeenth Century, Second Edition, The Tragical History of Doctor Faustuspg. 423 (see footnote 11) ISBN 978-1-55481-028-4

- ↑ Burton Russell 1992, p. 61

- ↑ Farnham, Willard. Twentieth Century Interpretations of Doctor Faustus. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc.,1969: 6.

- ↑ (Krstovic, J. O. and Marie Lazzardi. “Plot and Major Themes”. Rpt. In Literature Criticism from 1400 to 1800. Ed. Jelena O. Krstovic and Marie Lazzardi. Vol. 47. Farming Mills, MI: The Gale Group, 1999: 202)

- ↑ (Krstovic 8)