On November 6th, 2024, the 9,000th article was added to the SuccuWiki!

Satyr: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Definitions]] | [[Category:Definitions]] | ||

{{Infobox mythical creature | |||

|name = Satyr | |||

|image = Satyr maenad Louvre G34.jpg | |||

|caption = Satyr and maenad, shown on a red-figure Attic cup, ca. 510 BC–500 BC., Louvre, Paris, France | |||

|Grouping = Legendary creature | |||

|Sub_Grouping = Hybrid | |||

|Similar_creatures = Minotaur, Centaur, [[Harpy]] | |||

|Mythology = Greek mythology | |||

|Country = Greece | |||

|Habitat = Woodland and<br>mountains | |||

}} | |||

In Greek mythology, a '''satyr''' (UK /ˈsætə/, US /ˈseɪtər/; Greek: σάτυρος satyros, pronounced [sátyros]) is one one of a troop of ithyphallic male companions of Dionysus with horse-like (equine) features, including a horse-tail, horse-like ears, and sometimes a horse-like phallus. Early artistic representations sometimes include horse-like legs, but in 6th-century BC black-figure pottery human legs are the most common.<ref>Timothy Gantz (1996), ''Early Greek Myth'', p. 135.</ref> In Roman Mythology there is a concept similar to satyrs with goat-like features, the faun being half-man, half-goat. Greek-speaking Romans often used the Greek term ''saturos'' when referring to the Latin ''faunus'', and eventually syncretized the two. The female "[[Satyress]]es" were a late invention of poets — that roamed the woods and mountains.<ref name="Branham97p23">Branham (1997) [http://books.google.com/books?id=XrNEns3_yd0C&pg=PR23 p. xxiii]</ref> In myths they are often associated with pipe-playing. | |||

' | The satyrs' chief was Silenus, a minor deity associated (like Hermes and Priapus) with fertility. These characters can be found in the only complete remaining satyr play, ''Cyclops,'' by Euripides, and the fragments of Sophocles' ''Ichneutae'' (''Tracking Satyrs''). The satyr play was a short, lighthearted tailpiece performed after each trilogy of tragedies in Athenian festivals honoring Dionysus. There is not enough evidence to determine whether the satyr play regularly drew on the same myths as those dramatized in the tragedies that preceded. The groundbreaking tragic playwright Aeschylus is said to have been especially loved for his satyr plays, but none of them have survived. | ||

Attic painted vases depict mature satyrs as being strongly built with flat noses, large pointed ears, long curly hair, and full beards, with wreaths of vine or ivy circling their balding heads. Satyrs often carry the thyrsus: the rod of Dionysus tipped with a pine cone. | |||

Satyrs acquired their goat-like aspect through later Roman conflation with Faunus, a carefree Italic nature spirit of similar characteristics and identified with the Greek god Pan. Hence satyrs are most commonly described in Latin literature as having the upper half of a man and the lower half of a goat, with a goat's tail in place of the Greek tradition of horse-tailed satyrs; therefore, satyrs became nearly identical with fauns. Mature satyrs are often depicted in Roman art with goat's horns, while juveniles are often shown with bony nubs on their foreheads. | |||

About Satyrs, Praxiteles gives a new interpretation on the subject of free and carefree life. Instead of an elf with pointed ears and repulsive goat hooves, we face a child of nature, pure, but tame and fearless and brutal instincts necessary to enable it to defend itself against threats, and survives even without the help of modern civilization . Above all though, the Satyr with flute has a small companion for him, shows the deep connection with nature, the soft whistle of the wind, the sound of gurgling water of the crystal spring, the birds singing, or perhaps the singing a melody of a human soul that feeds higher feelings. | |||

As Dionysiac creatures they are lovers of wine and women, and they are ready for every physical pleasure. They roam to the music of pipes (''auloi''), cymbals, castanets, and bagpipes, and they love to chase maenads or bacchants (with whom they are obsessed, and whom they often pursue), or in later art, dance with the [[nymph]]s , and have a special form of dance called sikinnis. Because of their love of wine, they are often represented holding wine cups, and they appear often in the decorations on wine cups. | |||

==In Greek Mythology and Art== | |||

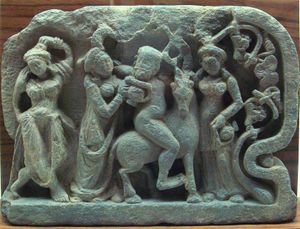

[[File:SatryWithWomen.jpg|thumb|Satyr on a mountain goat, drinking with women, in a Gandhara relief of 2nd-4th century CE]] | |||

In earlier Greek art, Silenos appear as old and ugly, but in later art, especially in works of the Attic school, this savage characteristic is softened into a more youthful and graceful aspect. | |||

This transformation or humanization of the Satyr appears throughout late Greek art. Another example of this shift occurs in the portrayal of Medusa and in that of the Amazon characters who are traditionally depicted as barbaric and uncivilized. A very humanized Satyr is depicted in a work of Praxiteles known as the "Resting Satyr". | |||

[ | Greek spirits [non-classical] known as Calicantsars have a noticeable resemblance to the ancient satyrs; they have goats' ears and the feet of donkeys or goats or horses, are covered with hair, and love women and the dance. | ||

Although they are not mentioned by Homer, in a fragment of Hesiod's works they are called brothers of the mountain nymphs and Kuretes, strongly connected with the cult of Dionysus. In the Dionysus cult, male followers are known as satyrs and female followers as maenads or bacchants. | |||

In Attica there was a species of drama known as the legends of gods and heroes, and the chorus was composed of satyrs and sileni. In the Athenian satyr plays of the 5th century BC, the chorus commented on the action. This "satyric drama" burlesqued the serious events of the mythic past with lewd pantomime and subversive mockery. One complete satyr play from the 5th century survives, the ''Cyclops'' of Euripides. | |||

The Satyr and the Traveller, one of Aesop's Fables, features the satyr as the benevolent host for a traveler in the forest in winter. The satyr is bewildered by the man's claim to be able to blow hot and cold with the same breath, first to warm his hands, then to cool his porridge, and turns him out for this inconstancy. | |||

A papyrus bearing a long fragment of a satyr play by Sophocles, given the title 'Tracking Satyrs' (''Ichneutae''), was found at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt, 1907. | |||

==In Roman Mythology and Art== | |||

Faunus were conflated in the popular and poetic imagination with Latin spirits of woodland and with the rustic Greek god Pan. Roman satyrs were described as goat-like from the haunches to the hooves, and were often pictured with larger horns, even ram's horns. Roman poets often conflated them with the fauns. | |||

Roman satire is a literary form, a poetic essay that was a vehicle for biting, subversive social and personal criticism. Though Roman satire is sometimes linked to the Greek satyr plays, satire's only connection to the satyric drama is through the subversive nature of the satyrs themselves, as forces in opposition to urbanity, decorum, and civilization itself. | |||

In | ==Other References== | ||

In many versions of the Bible, Isaiah 13:21 and 34:14, the English word "satyr" is used to represent the Hebrew ''se'irim'', "hairy ones," from "sa'ir" or "goat". There is an allusion to the practice of sacrificing to the se'irim (KJV "devils"; ASV "he-goats") in Leviticus 17:7. They may correspond to the "shaggy demon of the mountain-pass" (''azabb al-‘akaba'') of old Arab legend.<ref>"Satyrs," ''Encyclopaedia Britannica'', 11th ed. (1911), vol. 24, p. 234.</ref> It may otherwise refer to literal goats, and the worship of such.<ref>Palestine Exploration Quarterly, London, 1959, p. 57</ref> | |||

The savant Sir William Jones often refers to the Indian mythological Vānaras as satyrs/mountaineers in his translations of Sanskrit works. This view is generally held to be a mistake by present day researchers. | |||

==Baby Satyr== | |||

'''Baby satyrs''', or '''child satyrs''', are mythological creatures related to the satyr. They appear in popular folklore, classical artworks, film, and in various forms of local art. | |||

[[File:Ladysatyr.jpg|thumb|right|''Female Satyr Carrying Two Putti'' by Claude Michel (1738–1814)]] | |||

Some renaissance works depict young satyrs being tended to by older, sober satyrs, while there are also some representations of child satyrs taking part in Bacchanalian / Dionysian rituals (including drinking alcohol, playing musical instruments, and dancing). | |||

The presence of a baby or child satyr in a classical work, such as on a Greek vase, was mainly an aesthetic choice on the part of the artist. However, the role of a child in Greek art might imply a further meaning for baby satyrs: Eros, the son of Aphrodite, is consistently represented as a child or baby, and Bacchus, the divine sponsor of satyrs, is seen in numerous works as a baby, often in the company of the satyrs. A prominent instance of a baby satyr outside ancient Greece is Albrecht Dürer's 1505 engraving, "Musical Satyr and Nymph with Baby (Satyr's Family)". There is also a Victorian period napkin ring depicting a baby satyr next to a barrel, which further represents the perception of baby satyrs as partaking in the Bacchanalian festivities.<ref>''Revivals, Reveries, and Reconstructions: Images of Antiquity in Prints from 1500 to 1800'', [http://www.philamuseum.org/exhibitions/2000/30.html Philamuseum.org], exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.</ref> | |||

There are also many works of art of the rococo period depicting child or baby satyrs in Bacchanalian celebrations. Some works depict female satyrs with their children; others describe the child satyrs as playing an active role in the events, including one instance of a painting by Jean Raoux (1677–1735). "Mlle Prévost as a Bacchante" depicts a child satyr playing a tambourine while Mlle Prévost, a dancer at the Opéra, is dancing as part of the Bacchanal festivities.<ref>[http://www.unh.edu/music/Icon/igtamms.htm UNH.edu]</ref> | |||

==Satyrs and Orangutan== | |||

In the 17th century, the satyr legend came to be associated with stories of the orangutan, a great ape now found only in Sumatra and Borneo. Many early accounts which apparently refer to this animal describe the males as being sexually aggressive towards human women and towards females of its own species. The first scientific name given to this ape was ''Simia satyrus''.<ref>[http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v118/n2958/abs/118049b0.html C. W. Stiles. 1926. The zoological names ''Simia'', ''S. satyrus'', and ''Pithecus'', and their possible suppression. Nature 118, 49-49.]</ref> | |||

==Varieties== | |||

* Island Satyrs, which according to Pausanias<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.theoi.com/Thaumasios/SatyroiNesioi.html|title=Island Satyrs|accessdate=2008-12-28|work=Theoi Greek Mythology}}</ref> were a savage race of red-haired, satyr-like creatures from an isolated island chain. | |||

* Libyan Satyr, which according to Pliny the Elder<ref name="Libyan Aegipans & Satyrs">{{cite web|url=http://www.theoi.com/Thaumasios/SatyroiLibyes.html|title=Libyan Aegipans & Satyrs|accessdate=2008-12-28|work=Theoi Greek Mythology}}</ref> lived in Libya and resembled humans with long, pointed ears and horse tails, similar to the Greek nature-spirit satyrs. | |||

Medieval bestiaries also mention several varieties of satyrs, sometimes comparing them to apes or monkeys.<ref>Debra Hassing, "Sex in the Bestiaries," in ''The Mark of the Beast:The Medieval Bestiary in Art, Life, and Literature'' (New York: Garland Publishing, 1999), p. 73 and 88 (note 16); Willene B. Clark, ''A Medieval Book of Beasts. The Second-Family Bestiary: Commentary, Art, Text and Translation'' (Boydell Press, 2006), pp. 133–132.</ref> | |||

== | ==Notes== | ||

<references/> | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

* Harry Thurston Peck ''Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities'', 1898: "Faunus", "Pan", and "Silenus". | * Harry Thurston Peck ''Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities'', 1898: "Faunus", "Pan", and "Silenus". | ||

* Branham, R Bracht and Kinney, Daniel (1997) ''Introduction'' to Petronius' ''Satyrica'' [http://books.google.com/books?id=XrNEns3_yd0C&pg=PR13 pp.xiii-xxvi] | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

*[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Satyr The original source of this | *[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Satyr The original source of this article at Wikipedia] | ||

*[http://www.theoi.com/Georgikos/Satyroi.html Satyroi] | * [http://www.theoi.com/Georgikos/Satyroi.html Theoi Project: Satyroi] | ||

*[http://www.newanimal.org/satyr.htm Satyrs in Cryptozoology] | * [http://www.newanimal.org/satyr.htm Satyrs in Cryptozoology] | ||

*[http://jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=274&letter=S&search=Satyr Jewish Encyclopedia: Satyr] | * [http://jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=274&letter=S&search=Satyr Jewish Encyclopedia: Satyr] | ||

Revision as of 09:22, 30 July 2014

Satyr and maenad, shown on a red-figure Attic cup, ca. 510 BC–500 BC., Louvre, Paris, France | |

| Grouping | Legendary creature |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Hybrid |

| Similar creatures | Minotaur, Centaur, Harpy |

| Mythology | Greek mythology |

| Country | Greece |

| Habitat |

Woodland and mountains |

In Greek mythology, a satyr (UK /ˈsætə/, US /ˈseɪtər/; Greek: σάτυρος satyros, pronounced [sátyros]) is one one of a troop of ithyphallic male companions of Dionysus with horse-like (equine) features, including a horse-tail, horse-like ears, and sometimes a horse-like phallus. Early artistic representations sometimes include horse-like legs, but in 6th-century BC black-figure pottery human legs are the most common.[1] In Roman Mythology there is a concept similar to satyrs with goat-like features, the faun being half-man, half-goat. Greek-speaking Romans often used the Greek term saturos when referring to the Latin faunus, and eventually syncretized the two. The female "Satyresses" were a late invention of poets — that roamed the woods and mountains.[2] In myths they are often associated with pipe-playing.

The satyrs' chief was Silenus, a minor deity associated (like Hermes and Priapus) with fertility. These characters can be found in the only complete remaining satyr play, Cyclops, by Euripides, and the fragments of Sophocles' Ichneutae (Tracking Satyrs). The satyr play was a short, lighthearted tailpiece performed after each trilogy of tragedies in Athenian festivals honoring Dionysus. There is not enough evidence to determine whether the satyr play regularly drew on the same myths as those dramatized in the tragedies that preceded. The groundbreaking tragic playwright Aeschylus is said to have been especially loved for his satyr plays, but none of them have survived.

Attic painted vases depict mature satyrs as being strongly built with flat noses, large pointed ears, long curly hair, and full beards, with wreaths of vine or ivy circling their balding heads. Satyrs often carry the thyrsus: the rod of Dionysus tipped with a pine cone.

Satyrs acquired their goat-like aspect through later Roman conflation with Faunus, a carefree Italic nature spirit of similar characteristics and identified with the Greek god Pan. Hence satyrs are most commonly described in Latin literature as having the upper half of a man and the lower half of a goat, with a goat's tail in place of the Greek tradition of horse-tailed satyrs; therefore, satyrs became nearly identical with fauns. Mature satyrs are often depicted in Roman art with goat's horns, while juveniles are often shown with bony nubs on their foreheads.

About Satyrs, Praxiteles gives a new interpretation on the subject of free and carefree life. Instead of an elf with pointed ears and repulsive goat hooves, we face a child of nature, pure, but tame and fearless and brutal instincts necessary to enable it to defend itself against threats, and survives even without the help of modern civilization . Above all though, the Satyr with flute has a small companion for him, shows the deep connection with nature, the soft whistle of the wind, the sound of gurgling water of the crystal spring, the birds singing, or perhaps the singing a melody of a human soul that feeds higher feelings.

As Dionysiac creatures they are lovers of wine and women, and they are ready for every physical pleasure. They roam to the music of pipes (auloi), cymbals, castanets, and bagpipes, and they love to chase maenads or bacchants (with whom they are obsessed, and whom they often pursue), or in later art, dance with the nymphs , and have a special form of dance called sikinnis. Because of their love of wine, they are often represented holding wine cups, and they appear often in the decorations on wine cups.

In Greek Mythology and Art

In earlier Greek art, Silenos appear as old and ugly, but in later art, especially in works of the Attic school, this savage characteristic is softened into a more youthful and graceful aspect.

This transformation or humanization of the Satyr appears throughout late Greek art. Another example of this shift occurs in the portrayal of Medusa and in that of the Amazon characters who are traditionally depicted as barbaric and uncivilized. A very humanized Satyr is depicted in a work of Praxiteles known as the "Resting Satyr".

Greek spirits [non-classical] known as Calicantsars have a noticeable resemblance to the ancient satyrs; they have goats' ears and the feet of donkeys or goats or horses, are covered with hair, and love women and the dance.

Although they are not mentioned by Homer, in a fragment of Hesiod's works they are called brothers of the mountain nymphs and Kuretes, strongly connected with the cult of Dionysus. In the Dionysus cult, male followers are known as satyrs and female followers as maenads or bacchants.

In Attica there was a species of drama known as the legends of gods and heroes, and the chorus was composed of satyrs and sileni. In the Athenian satyr plays of the 5th century BC, the chorus commented on the action. This "satyric drama" burlesqued the serious events of the mythic past with lewd pantomime and subversive mockery. One complete satyr play from the 5th century survives, the Cyclops of Euripides.

The Satyr and the Traveller, one of Aesop's Fables, features the satyr as the benevolent host for a traveler in the forest in winter. The satyr is bewildered by the man's claim to be able to blow hot and cold with the same breath, first to warm his hands, then to cool his porridge, and turns him out for this inconstancy.

A papyrus bearing a long fragment of a satyr play by Sophocles, given the title 'Tracking Satyrs' (Ichneutae), was found at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt, 1907.

In Roman Mythology and Art

Faunus were conflated in the popular and poetic imagination with Latin spirits of woodland and with the rustic Greek god Pan. Roman satyrs were described as goat-like from the haunches to the hooves, and were often pictured with larger horns, even ram's horns. Roman poets often conflated them with the fauns.

Roman satire is a literary form, a poetic essay that was a vehicle for biting, subversive social and personal criticism. Though Roman satire is sometimes linked to the Greek satyr plays, satire's only connection to the satyric drama is through the subversive nature of the satyrs themselves, as forces in opposition to urbanity, decorum, and civilization itself.

Other References

In many versions of the Bible, Isaiah 13:21 and 34:14, the English word "satyr" is used to represent the Hebrew se'irim, "hairy ones," from "sa'ir" or "goat". There is an allusion to the practice of sacrificing to the se'irim (KJV "devils"; ASV "he-goats") in Leviticus 17:7. They may correspond to the "shaggy demon of the mountain-pass" (azabb al-‘akaba) of old Arab legend.[3] It may otherwise refer to literal goats, and the worship of such.[4]

The savant Sir William Jones often refers to the Indian mythological Vānaras as satyrs/mountaineers in his translations of Sanskrit works. This view is generally held to be a mistake by present day researchers.

Baby Satyr

Baby satyrs, or child satyrs, are mythological creatures related to the satyr. They appear in popular folklore, classical artworks, film, and in various forms of local art.

Some renaissance works depict young satyrs being tended to by older, sober satyrs, while there are also some representations of child satyrs taking part in Bacchanalian / Dionysian rituals (including drinking alcohol, playing musical instruments, and dancing).

The presence of a baby or child satyr in a classical work, such as on a Greek vase, was mainly an aesthetic choice on the part of the artist. However, the role of a child in Greek art might imply a further meaning for baby satyrs: Eros, the son of Aphrodite, is consistently represented as a child or baby, and Bacchus, the divine sponsor of satyrs, is seen in numerous works as a baby, often in the company of the satyrs. A prominent instance of a baby satyr outside ancient Greece is Albrecht Dürer's 1505 engraving, "Musical Satyr and Nymph with Baby (Satyr's Family)". There is also a Victorian period napkin ring depicting a baby satyr next to a barrel, which further represents the perception of baby satyrs as partaking in the Bacchanalian festivities.[5]

There are also many works of art of the rococo period depicting child or baby satyrs in Bacchanalian celebrations. Some works depict female satyrs with their children; others describe the child satyrs as playing an active role in the events, including one instance of a painting by Jean Raoux (1677–1735). "Mlle Prévost as a Bacchante" depicts a child satyr playing a tambourine while Mlle Prévost, a dancer at the Opéra, is dancing as part of the Bacchanal festivities.[6]

Satyrs and Orangutan

In the 17th century, the satyr legend came to be associated with stories of the orangutan, a great ape now found only in Sumatra and Borneo. Many early accounts which apparently refer to this animal describe the males as being sexually aggressive towards human women and towards females of its own species. The first scientific name given to this ape was Simia satyrus.[7]

Varieties

- Island Satyrs, which according to Pausanias[8] were a savage race of red-haired, satyr-like creatures from an isolated island chain.

- Libyan Satyr, which according to Pliny the Elder[9] lived in Libya and resembled humans with long, pointed ears and horse tails, similar to the Greek nature-spirit satyrs.

Medieval bestiaries also mention several varieties of satyrs, sometimes comparing them to apes or monkeys.[10]

Notes

- ↑ Timothy Gantz (1996), Early Greek Myth, p. 135.

- ↑ Branham (1997) p. xxiii

- ↑ "Satyrs," Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th ed. (1911), vol. 24, p. 234.

- ↑ Palestine Exploration Quarterly, London, 1959, p. 57

- ↑ Revivals, Reveries, and Reconstructions: Images of Antiquity in Prints from 1500 to 1800, Philamuseum.org, exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- ↑ UNH.edu

- ↑ C. W. Stiles. 1926. The zoological names Simia, S. satyrus, and Pithecus, and their possible suppression. Nature 118, 49-49.

- ↑ "Island Satyrs". Theoi Greek Mythology. http://www.theoi.com/Thaumasios/SatyroiNesioi.html. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ "Libyan Aegipans & Satyrs". Theoi Greek Mythology. http://www.theoi.com/Thaumasios/SatyroiLibyes.html. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ Debra Hassing, "Sex in the Bestiaries," in The Mark of the Beast:The Medieval Bestiary in Art, Life, and Literature (New York: Garland Publishing, 1999), p. 73 and 88 (note 16); Willene B. Clark, A Medieval Book of Beasts. The Second-Family Bestiary: Commentary, Art, Text and Translation (Boydell Press, 2006), pp. 133–132.

References

- Harry Thurston Peck Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1898: "Faunus", "Pan", and "Silenus".

- Branham, R Bracht and Kinney, Daniel (1997) Introduction to Petronius' Satyrica pp.xiii-xxvi