On November 27th, 2022, the 8,000th article was added to the SuccuWiki!

Kitsune

This article is taken from the Wikipedia entry here.

Kitsune is the Japanese word for fox. Foxes are a common subject of Japanese folklore. Stories depict them as intelligent beings and as possessing magical abilities that increase with their age and wisdom. Foremost among these is the ability to assume human form. While some folktales speak of kitsune employing this ability to trick others — as foxes in folklore often do — others portray them as faithful guardians, friends, lovers, and wives.

Foxes and human beings lived in close proximity in ancient Japan; this companionship gave rise to legends about the creatures. Kitsune have become closely associated with Inari, a Shinto kami or spirit, and serve as his messengers. This role has reinforced the fox's supernatural significance. The more tails a kitsune has — they may have as many as nine — the older, wiser, and more powerful it is. Because of their potential power and influence, some people make offerings to them as to a deity.

Origins

There is debate whether the kitsune myths originated entirely from foreign sources or are in part an indigenous Japanese concept dating as far back as the fifth century BC. It is widely agreed that at least some fox myths in Japan can be traced to China, Korea, or India. Many of the earliest surviving stories are recorded in the Konjaku Monogatari, an 11th-century collection of Chinese, Indian, and Japanese narratives.[1] Chinese folk tales tell of kitsune-like fox spirits that may have up to nine tails.

In contrast, Japanese folklorist Kiyoshi Nozaki argues that the Japanese regarded kitsune positively as early as the 4th century A.D.; the only things imported from China or Korea were the kitsune's negative attributes.[2] He states that, according to a 16th-century book of records called the Nihon Ryakki, foxes and human beings lived in close proximity in ancient Japan, and he contends that indigenous legends about the creatures arose as a result.[3] Inari scholar Karen Smyers notes that the idea of the fox as seductress and the connection of the fox myths to Buddhism were introduced into Japanese folklore through similar Chinese stories, but she maintains that some fox stories contain elements unique to Japan.[4]

Etymology

The full etymology is unknown. The oldest known usage of the word is in the 794 text Shin'yaku Kegonkyō Ongi Shiki (新訳華厳経音義私記). Other old sources include Nihon Ryōiki (810–824) and Wamyō Ruijushō (c. 934). These oldest sources are written in Man'yōgana which clearly identifies the historical spelling as ki1tune. Following several diachronic phonological changes, this becomes kitsune.

Many etymological suggestions have been made; however, there is no general agreement.

- Myōgoki (1268) suggests that it is so called because it is "always (tsune) yellow (ki)".

- Early Kamakura period Mizukagami indicates that it means "came (ki) [perfective case particle tsu] to bedroom (ne)" due to a legend that a kitsune would change into one's wife and bear children.

- Arai Hakuseki in Tōga (1717) suggests that ki means "stench", tsu is a possessive particle, and ne is related to inu, the word for "dog".

- Tanikawa Kotosuga in Wakun no Shiori (1777–1887) suggests that ki means "yellow", tsu is a possessive particle, and ne is related to neko, the word for cat.

- Ōtsuki Fumihiko in Daigenkai (1932–1935) proposes that kitsu is an onomatopoeia for the animal, and that ne is an affix or an honorific word meaning a servant of an Inari shrine.

According to Nozaki, the word kitsune was originally onomatopoeia.[3] Kitsu represented a fox's yelp and came to be the general word for fox. -Ne signifies an affectionate mood, which Nozaki presents as further evidence of an established, non-imported tradition of benevolent foxes in Japanese folklore.[2] Kitsu is now archaic; in modern Japanese, a fox's cry is transcribed as kon kon or gon gon.

One of the oldest surviving kitsune tales provides a widely known folk etymology of the word kitsune; the story is now known to be false.[5] Unlike most tales of kitsune who become human and marry human males, this one does not end tragically:[6][7]

| “ | Ono, an inhabitant of Mino (says an ancient Japanese legend of A.D. 545), spent the seasons longing for his ideal of female beauty. He met her one evening on a vast moor and married her. Simultaneously with the birth of their son, Ono's dog was delivered of a pup which as it grew up became more and more hostile to the lady of the moors. She begged her husband to kill it, but he refused. At last one day the dog attacked her so furiously that she lost courage, resumed vulpine shape, leaped over a fence and fled. "You may be a fox," Ono called after her, "but you are the mother of my son and I love you. Come back when you please; you will always be welcome." So every evening she stole back and slept in his arms.[5] |

” |

Because the fox returns to her husband each night as a woman but leaves each morning as a fox, she is called Kitsune. In classical Japanese, kitsu-ne means come and sleep, and ki-tsune means always comes.[7]

Characteristics

Kitsune are believed to possess superior intelligence, long life, and magical powers. They are a type of yōkai, or spiritual entity, and the word kitsune is often translated as fox spirit. However, this does not mean that kitsune are ghosts, nor that they are fundamentally different from regular foxes. Because the word spirit is used to reflect a state of knowledge or enlightenment, all long-lived foxes gain supernatural abilities.[4]

There are two common classifications of kitsune. The myōbu are benevolent, celestial foxes associated with Inari; they are sometimes simply called Inari foxes. On the other hand, the wild nogitsune (野狐, literally, field foxes) tend to be mischievous or even malicious.[8] Local traditions add further types.[8] For example, a ninko is an invisible fox spirit that human beings can only perceive when it possesses them. Another tradition classifies kitsune into one of thirteen types defined by which supernatural abilities the kitsune possesses.[9][10]

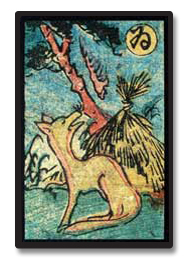

Physically, kitsune are noted for having as many as nine tails.[11] Generally, a greater number of tails indicates an older and more powerful fox; in fact, some folktales say that a fox will only grow additional tails after it has lived 1,000 years.[12] One, five, seven, and nine tails are the most common numbers in folk stories.[13] When a kitsune gains its ninth tail, its fur becomes white or gold.[11] These kyūbi no kitsune (nine-tailed foxes) gain the abilities to see and hear anything happening anywhere in the world. Other tales attribute them infinite wisdom (omniscience).[14]

A kitsune may take on human form, an ability learned when it reaches a certain age — usually 100 years, although some tales say 50.[12] As a common prerequisite for the transformation, the fox must place reeds, a broad leaf, or a skull over its head.[15] Common forms assumed by kitsune include beautiful women, young girls, or elderly men. These shapes are not limited by the fox's age or gender,[4] and a kitsune can duplicate the appearance of a specific person.[16] Foxes are particularly renowned for impersonating beautiful women. Common belief in medieval Japan was that any woman encountered alone, especially at dusk or night, could be a fox.[17]

In some stories, kitsune have difficulty hiding their tails when they take human form; looking for the tail, perhaps when the fox gets drunk or careless, is a common method of discerning the creature's true nature.[18] Variants on the theme have the kitsune retain other foxlike traits, such as a coating of fine hair, a fox-shaped shadow, or a reflection that shows its true form.[19] Kitsune-gao or fox-faced refers to human females who have a narrow face with close-set eyes, thin eyebrows, and high cheekbones. Traditionally, this facial structure is considered attractive, and some tales ascribe it to foxes in human form.[20] Kitsune have a fear and hatred of dogs even while in human form, and some become so rattled by the presence of dogs that they revert to the shape of a fox and flee. A particularly devout individual may be able to see through a fox's disguise automatically.[21]

One folk story illustrating these imperfections in the kitsune's human shape concerns Koan, a historical person credited with wisdom and magical powers of divination. According to the story, he was staying at the home of one of his devotees when he scalded his foot entering a bath because the water had been drawn too hot. Then, "in his pain, he ran out of the bathroom naked. When the people of the household saw him, they were astonished to see that Koan had fur covering much of his body, along with a fox's tail. Then Koan transformed in front of them, becoming an elderly fox and running away."[22]

Other supernatural abilities commonly attributed to the kitsune include possession, mouths or tails that generate fire or lightning (known as kitsune-bi; literally, fox-fire), willful manifestation in the dreams of others, flight, invisibility, and the creation of illusions so elaborate as to be almost indistinguishable from reality.[19][15] Some tales speak of kitsune with even greater powers, able to bend time and space, drive people mad, or take fantastic shapes such as a tree of incredible height or a second moon in the sky.[23][24] Other kitsune have characteristics reminiscent of vampires or succubi and feed on the life or spirit of human beings, generally through sexual contact.[25]

Kitsunetsuki

Kitsunetsuki (狐憑き or 狐付き; also written kitsune-tsuki) literally means the state of being possessed by a fox. The victim is typically a young woman, whom the fox enters beneath her fingernails or through her breasts.[26] In some cases, the victims' facial expressions are said to change in such a way that they resemble those of a fox. Japanese tradition holds that fox possession can cause illiterate victims to temporarily gain the ability to read.[27]

Folklorist Lafcadio Hearn describes the condition in the first volume of his Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan:

| “ | Strange is the madness of those into whom demon foxes enter. Sometimes they run naked shouting through the streets. Sometimes they lie down and froth at the mouth, and yelp as a fox yelps. And on some part of the body of the possessed a moving lump appears under the skin, which seems to have a life of its own. Prick it with a needle, and it glides instantly to another place. By no grasp can it be so tightly compressed by a strong hand that it will not slip from under the fingers. Possessed folk are also said to speak and write languages of which they were totally ignorant prior to possession. They eat only what foxes are believed to like — tofu, aburagé, azukimeshi, etc. — and they eat a great deal, alleging that not they, but the possessing foxes, are hungry.[28] | ” |

He goes on to note that, once freed from the possession, the victim will never again be able to eat tofu, azukimeshi, or other foods favored by foxes.

Exorcism, often performed at an Inari shrine, may induce a fox to leave its host.[29] In the past, when such gentle measures failed or a priest was not available, victims of kitsunetsuki were beaten or badly burned in hopes of forcing the fox to leave. Entire families were ostracized by their communities after a member of the family was thought to be possessed.[28]

In Japan, kitsunetsuki was noted as a disease as early as the Heian period and remained a common diagnosis for mental illness until the early 20th century.[30][31] Possession was the explanation for the abnormal behavior displayed by the afflicted individuals. In the late 19th century, Dr. Shunichi Shimamura noted that physical diseases that caused fever were often considered kitsunetsuki.[32] The belief has lost favor, but stories of fox possession still appear in the tabloid press and popular media. One notable occasion involved allegations that members of the Aum Shinrikyo cult had been possessed.[33]

In medicine, kitsunetsuki is an ethnic psychosis unique to Japanese culture. Those who suffer from the condition believe they are possessed by a fox.[34] Symptoms include cravings for rice or sweet red beans, listlessness, restlessness, and aversion to eye contact. Kitsunetsuki is similar to but distinct from clinical lycanthropy.[35]

Hoshi no tama

Depictions of kitsune or their possessed victims may feature round or onion-shaped white balls known as hoshi no tama (star balls). Tales describe these as glowing with kitsune-bi, or fox-fire.[36] Some stories identify them as magical jewels or pearls.[37] When not in human form or possessing a human, a kitsune keeps the ball in its mouth or carries it on its tail.[12] Jewels are a common symbol of Inari, and representations of sacred Inari foxes without them are rare.[38]

One belief is that when a kitsune changes shape, its hoshi no tama holds a portion of its magical power. Another tradition is that the pearl represents the kitsune's soul; the kitsune will die if separated from it for long. Those who obtain the ball may be able to extract a promise from the kitsune to help them in exchange for its return.[39] For example, a 12th-century tale describes a man using a fox's hoshi no tama to secure a favor:

| “ | "Confound you!" snapped the fox. "Give me back my ball!" The man ignored its pleas till finally it said tearfully, "All right, you've got the ball, but you don't know how to keep it. It won't be any good to you. For me, it's a terrible loss. I tell you, if you don't give it back, I'll be your enemy forever. If you do give it back though, I'll stick to you like a protector god." | ” |

The fox later saves his life by leading him past a band of armed bandits.[40]

Portrayal

Servants of Inari

Kitsune are associated with Inari, the Shinto deity of rice.[41] This association has reinforced the fox's supernatural significance.[42] Originally, kitsune were Inari's messengers, but the line between the two is now blurred so that Inari himself may be depicted as a fox. Likewise, entire shrines are dedicated to kitsune, where devotees can leave offerings.[8] Fox spirits are particularly fond of a fried sliced tofu called aburage, which is accordingly found in kitsune udon and kitsune soba. Similarly, Inari-zushi is a type of sushi named for Inari that consists of rice-filled pouches of fried tofu.[43] There is speculation among folklorists as to whether another Shinto fox deity existed in the past. Foxes have long been worshipped as kami.[44]

Inari's kitsune are white, a color of good omen.[8] They possess the power to ward off evil, and they sometimes serve as guardian spirits. In addition to protecting Inari shrines, they are petitioned to intervene on behalf of the locals and particularly to aid against troublesome nogitsune. Black foxes and nine-tailed foxes are likewise considered good omens.[18]

According to beliefs derived from fusui (feng shui), the fox's power over evil is such that a mere statue of a fox can dispel the evil kimon, or energy, that flows from the northeast. Many Inari shrines, such as the famous Fushimi Inari shrine in Kyoto, feature such statues, sometimes large numbers of them.

Kitsune are connected to the Buddhist religion through the Dakiniten, goddesses conflated with Inari's female aspect. Dakiniten is depicted as a female boddhisattva wielding a sword and riding a flying white fox.[45]

Tricksters

Kitsune are often presented as tricksters, with motives that vary from mischief to malevolence. Stories tell of kitsune playing tricks on overly proud samurai, greedy merchants, and boastful commoners, while the crueler ones abuse poor tradesmen and farmers or devout Buddhist monks. Their victims are usually men; women are possessed instead.[17] For example, kitsune are thought to employ their kitsune-bi or fox-fire to lead travelers astray in the manner of a will o' the wisp.[46][47] Another tactic is for the kitsune to confuse its target with illusions or visions.[17] Other common goals of trickster kitsune include seduction, theft of food, humiliation of the prideful, or vengeance for a perceived slight.

A traditional game called kitsune-ken (fox-fist) references the kitsune's powers over human beings. The game is similar to rock, paper, scissors, but the three hand positions signify a fox, a hunter, and a village headman. The headman beats the hunter, whom he outranks; the hunter beats the fox, whom he shoots; the fox beats the headman, whom he bewitches.[48][49]

This ambiguous portrayal, coupled with their reputation for vengefulness, leads people to try to discover a troublesome fox's motives. In one case, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a high government official, wrote a letter to the kami Inari:

| “ | To Inari Daimyojin, My lord, I have the honor to inform you that one of the foxes under your jurisdiction has bewitched one of my servants, causing her and others a great deal of trouble. I have to request that you make minute inquiries into the matter, and endeavor to find out the reason of your subject misbehaving in this way, and let me know the result. If it turns out that the fox has no adequate reason to give for his behavior, you are to arrest and punish him at once. If you hesitate to take action in this matter I shall issue orders for the destruction of every fox in the land. Any other particulars that you may wish to be informed of in reference to what has occurred, you can learn from the high priest of Yoshida.[50] |

” |

Kitsune keep their promises and strive to repay any favor. Occasionally a kitsune attaches itself to a person or household, where they can cause all sorts of mischief. In one story from the 12th century, only the homeowner's threat to exterminate the foxes convinces them to behave. The kitsune patriarch appears in the man's dreams:

| “ | "My father lived here before me, sir, and by now I have many children and grandchildren. They get into a lot of mischief, I'm afraid, and I'm always after them to stop, but they never listen. And now, sir, you're understandably fed up with us. I gather that you're going to kill us all. But I just want you to know, sir, how sorry I am that this is our last night of life. Won't you pardon us, one more time? If we ever make trouble again, then of course you must act as you think best. But the young ones, sir — I'm sure they'll understand when I explain to them why you're so upset. We'll do everything we can to protect you from now on, if only you'll forgive us, and we'll be sure to let you know when anything good is going to happen!"[51] | ” |

Other kitsune use their magic for the benefit of their companion or hosts as long as the human beings treat them with respect. As yōkai, however, kitsune do not share human morality, and a kitsune who has adopted a house in this manner may, for example, bring its host money or items that it has stolen from the neighbors. Accordingly, common households thought to harbor kitsune are treated with suspicion.[52] Oddly, samurai families were often reputed to share similar arrangements with kitsune, but these foxes were considered myōbu and the use of their magic a sign of prestige.[53] Abandoned homes were common haunts for kitsune.[17] One 12th-century story tells of a minister moving into an old mansion only to discover a family of foxes living there. They first try to scare him away, then claim that the house "has been ours for many years, and . . . we wish to register a vigorous protest." The man refuses, and the foxes resign themselves to moving to an abandoned lot nearby.[54]

Tales distinguish kitsune gifts from kitsune payments. If a kitsune offers a payment or reward that includes money or material wealth, part or all of the sum will consist of old paper, leaves, twigs, stones, or similar valueless items under a magical illusion.[55][56] True kitsune gifts are usually intangibles, such as protection, knowledge, or long life.[56]

Wives and lovers

Kitsune are commonly portrayed as lovers, usually in stories involving a young human male and a kitsune who takes the form of a human woman.[57] The kitsune may be a seductress, but these stories are more often romantic in nature.[58] Typically, the young man unknowingly marries the fox, who proves a devoted wife. The man eventually discovers the fox's true nature, and the fox-wife is forced to leave him. In some cases, the husband wakes as if from a dream, filthy, disoriented, and far from home. He must then return to confront his abandoned family in shame.

Many stories tell of fox-wives bearing children. When such progeny are human, they possess special physical or supernatural qualities that often pass to their own children.[18] The astrologer-magician Abe no Seimei was reputed to have inherited such extraordinary powers.[59]

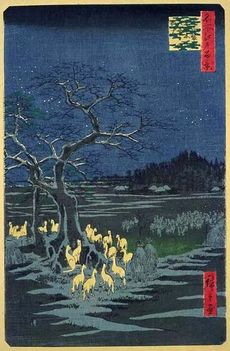

Other stories tell of kitsune marrying one another. Rain falling from a clear sky — a sunshower — is sometimes called kitsune no yomeiri or the kitsune's wedding, in reference to a folktale describing a wedding ceremony between the creatures being held during such conditions.[60] The event is considered a good omen, but the kitsune will seek revenge on any uninvited guests.[61]

Stephen Turnbull, in "Nagashino 1575", relates the tale of the Takeda clan's involvement with a fox-woman. The warlord Takeda Shingen, in 1544, defeated in battle a lesser local warlord named Suwa Yorishige and drove him to suicide after a "humiliating and spurious" peace conference, after which Shingen forced marriage on his beautiful 14-year-old daughter Lady Koi--Shingen's own niece. Shingen, Turnbull writes, "was so obsessed with the girl that his superstitious followers became alarmed and believed her to be an incarnation of the white fox-spirit of the Suwa Shrine, who had bewitched him in order to gain revenge." When their son Takeda Katsuyori proved to be a disastrous leader and led the clan to their devastating defeat at the battle of Nagashino, Turnbull writes, "wise old heads nodded, remembering the unhappy circumstances of his birth and his magical mother".

In fiction

Embedded in Japanese folklore as they are, kitsune appear in numerous Japanese works. Noh, kyogen, bunraku, and kabuki plays derived from folk tales feature them,[62][63] as do contemporary works such as anime, manga and video games. Western authors of fiction have begun to make use of the kitsune legends. Although these portrayals vary considerably, kitsune are generally depicted in accordance with folk stories, as wise, cunning, and powerful beings.

Kuzunoha, mother of Abe no Seimei, is a well-known kitsune character in traditional Japanese theater. She is featured in the five-part bunraku and kabuki play Ashiya Dōman Ōuchi Kagami (The Mirror of Ashiya Dōman and Ōuchi). The fourth part, Kuzunoha or The Fox of Shinoda Wood, is often performed independently of the other scenes and tells of the discovery of Kuzunoha's kitsune nature and her subsequent departure from her husband and child.[64][65]

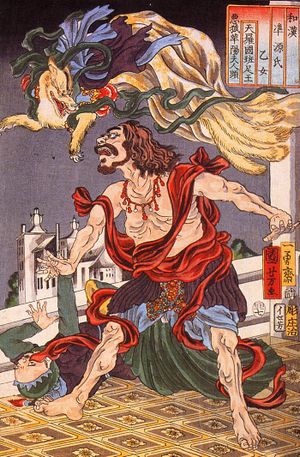

Tamamo-no-Mae is the subject of the noh drama Sesshoseki (The Death Stone) and of kabuki and kyogen plays titled Tamamonomae (The Beautiful Fox Witch). Tamamo-no-Mae commits evil deeds in India, China, and Japan but is discovered and dies. Her spirit transforms into the "killing stone" of the noh play's title. She is eventually redeemed by the Buddhist priest Gennō.[66][67][68]

Genkurō is a kitsune renowned for his filial piety. In the bunraku and kabuki drama Yoshitsune Sembon Zakura (Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Trees), Yoshitsune's lover, Lady Shizuka, owns a hand-drum made from the skins of Genkuro's parents. The fox takes human form and becomes his retainer, Satō Tadanobu, but his identity is revealed. The kitsune explains that he hears the voice of his parents when the drum is struck. Yoshitsune and Shizuka give him the drum, so Genkuro grants Yoshitsune magical protection.[69][70][71]

References

- ↑ Goff, Janet. "Foxes in Japanese culture: beautiful or beastly?" Japan Quarterly 44:2 (April-June 1997).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Nozaki, Kiyoshi. Kitsune — Japan's Fox of Mystery, Romance, and Humor. Tokyo: The Hokuseidô Press, 1961. 5

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Nozaki. Kitsune. 3

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Smyers, Karen Ann. The Fox and the Jewel: Shared and Private Meanings in Contemporary Japanese Inari Worship. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1999. 127–128

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Hamel, Frank. Human Animals: Werewolves & Other Transformations. New Hyde Park, N.Y.: University Books, 1969. 89

- ↑ Goff. "Foxes". Japan Quarterly 44:2

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Smyers. The Fox and the Jewel. 72

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Hearn, Lafcadio. Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan. Project Gutenberg e-text edition, 2005. 154

- ↑ Hall, Jamie. Half Human, Half Animal: Tales of Werewolves and Related Creatures. Bloomington, Indiana: Authorhouse, 2003. 139

- ↑ Nozaki. Kitsune. 211–212

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Smyers. The Fox and the Jewel. 129

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Hamel. Human Animals. 91

- ↑ "Kitsune, Kumiho, Huli Jing, Fox" (html). 2003-04-28. http://academia.issendai.com/fox-misconceptions.shtml#tails. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ↑ Hearn. Glimpses. 159

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Nozaki. Kitsune. 25–26

- ↑ Hall. Half Human. 145

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Tyler xlix.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Ashkenazy, Michael. Handbook of Japanese Mythology. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio, 2003. 148

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Hearn. Glimpses. 155

- ↑ Nozaki. Kitsune. 95, 206

- ↑ Heine, Steven. Shifting Shape, Shaping Text: Philosophy and Folklore in the Fox Koan. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1999. 153

- ↑ Hall. Half Human. 144

- ↑ Hearn. Glimpses. 156–157

- ↑ Nozaki. Kitsune. 36–37

- ↑ Nozaki. Kitsune. 26, 221

- ↑ Nozaki. Kitsune. 59

- ↑ Nozaki. Kitsune. 216

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Hearn. Glimpses. 158

- ↑ Smyers. The Fox and the Jewel. 90

- ↑ Nozaki. Kitsune. 211

- ↑ Hearn. Glimpses. 165

- ↑ Nozaki. Kitsune. 214–215

- ↑ Downey, Jean Miyake. "Ten Thousand Things." Kyoto Journal 63. Retrieved on December 13 2006.

- ↑ Haviland, William A. Cultural Anthropology, 10th ed. New York: Wadsworth Publishing Co., 2002. 144–145

- ↑ Yonebayashi, T. "Kitsunetsuki (Possession by Foxes)". Transcultural Psychiatry 1:2 (1964). 95–97

- ↑ Nozaki. Kitsune. 183

- ↑ Nozaki. Kitsune. 169–170

- ↑ Smyers. The Fox and the Jewel. 112–114

- ↑ Hall. Half Human. 149

- ↑ Tyler 299–300.

- ↑ Smyers. The Fox and the Jewel. 76

- ↑ Hearn. Glimpses. 153

- ↑ Smyers. The Fox and the Jewel. 96

- ↑ Smyers. The Fox and the Jewel. 77, 81

- ↑ Smyers. The Fox and the Jewel. 82–85

- ↑ Addiss, Stephen. Japanese Ghosts & Demons: Art of the Supernatural. New York: G. Braziller, 1985. 137

- ↑ Hall. Half Human. 142

- ↑ Nozaki. Kitsune. 230

- ↑ Smyers. The Fox and the Jewel. 98

- ↑ Hall. Half Human. 137

- ↑ Tyler 114–5.

- ↑ Hearn. Glimpses. 159–161

- ↑ Hall. Half Human. 148

- ↑ Tyler 122–4.

- ↑ Nozaki. Kitsune. 195

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Smyers. The Fox and the Jewel. 103–105

- ↑ Hamel. Human Animals. 90

- ↑ Hearn. Glimpses. 157

- ↑ Ashkenazy. Handbook. 150

- ↑ Addiss. Ghosts & Demons. 132

- ↑ Vaux, Bert. "Sunshower summary". LINGUIST List 9.1795 (Dec. 1998). A compilation of terms for sun showers from various cultures and languages. Retrieved on December 13 2006.

- ↑ Hearn. Glimpses. 162–163

- ↑ Nozaki. Kitsune. 109–124

- ↑ Nozaki. Kitsune. 110–111

- ↑ "Ashiya Dōman Ōuchi Kagami" (php). Kabuki21.com. http://www.kabuki21.com/adok.php. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

- ↑ Nozaki. Kitsune. 112–113, 122–123

- ↑ "Noh synopsis: Sesshoseki" (html). The Mibu-Dera Kyogen Pantomimes. http://www.yamanakart.com/egg-p/mibu/pages/plays/noh.html#Anchor-SESSHOSEKI-48213. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

- ↑ "Tamamonomae Pantomime" (html). The Mibu-Dera Kyogen Pantomimes. http://www.yamanakart.com/egg-p/mibu/pages/plays/tamamonomae.html. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

- ↑ Nozaki. Kitsune. 114–116

- ↑ Ashkenazy. Handbook. 150

- ↑ "Yoshinoyama: Yoshitsune Sembon Zakura" (php). Kabuki21.com. http://www.kabuki21.com/yoshinoyama.php. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

Other sources

- Addiss, Stephen. Japanese Ghosts & Demons: Art of the Supernatural. New York: G. Braziller, 1985. (pp. 132–137) ISBN 0-8076-1126-3

- Ashkenazy, Michael. Handbook of Japanese Mythology. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio, 2003. ISBN 1-57607-467-6

- Bathgate, Michael. The Fox's Craft in Japanese Religion and Folklore: Shapeshifters, Transformations, and Duplicities. New York: Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0-415-96821-6

- Hall, Jamie. Half Human, Half Animal: Tales of Werewolves and Related Creatures. Bloomington, Indiana: Authorhouse, 2003. (pp. 121–152) ISBN 1-4107-5809-5

- Hamel, Frank. Human Animals: Werewolves & Other Transformations. New Hyde Park, N.Y.: University Books, 1969. (pp. 88–102) ISBN 0-7661-6700-3

- Hearn, Lafcadio. Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan. Project Gutenberg e-text edition, 2005. Retrieved on November 20, 2006.

- Heine, Steven. Shifting Shape, Shaping Text: Philosophy and Folklore in the Fox Koan. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8248-2150-5

- Johnson, T.W. "Far Eastern Fox Lore". Asian Folklore Studies 33:1 (1974)

- Nozaki, Kiyoshi. Kitsuné — Japan's Fox of Mystery, Romance, and Humor. Tokyo: The Hokuseidô Press. 1961.

- http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/oinari.shtml

- Smyers, Karen Ann. The Fox and the Jewel: Shared and Private Meanings in Contemporary Japanese Inari Worship. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8248-2102-5

- Turnbull, Stephen. Nagashino 1575. Osprey Publishing, Great Britain, 2000. ISBN 1-84176-250-4.

- Tyler, Royall (ed. and trans.) Japanese Tales. New York: Pantheon Books, 1987. ISBN 0-394-75656-8

External links

- The Kitsune Page

- Foxtrot's Guide to Kitsune Lore

- Kitsune.org folklore

- Kitsune, Kumiho, Huli Jing, Fox - Fox spirits in Asia, and Asian fox spirits in the West An extensive bibliography of fox-spirit books.

- Portal of Transformation: Kitsune in Folklore and Mythology

- IDEAS Undergraduate On-Line Journal